| WYOMING |

While visiting Fort Laramie, take a detour to view another facet of its long and fascinating history at a lesser-known and more scandalous slice of Fort Laramie.

| THE REGIMENTAL MASCOT

Just three miles west of historic Fort Laramie—purchased by the U.S. government from the American Fur Company in 1849 for $4,000 (about $152,000 in today’s money)—sits one of the more notorious and colorful landmarks of Wyoming’s frontier past: the Three Mile Hog Ranch. Though now on private land, the site remains a fascinating side trip down a gravel road for those curious about one of the last surviving military bordellos in the American West.

The ranch began in 1873 when two Swiss immigrants, Jules Ecoffey and Adolph Cuny, established a trading post and saloon on the banks of the Laramie River. By 1874, the outpost had expanded its business, bringing in prostitutes to cater to the soldiers stationed at Fort Laramie. At any given time, at least ten “ladies of the night” lived and worked there, making the Hog Ranch infamous on the plains.

Among those associated with the site was Martha Jane Cannary, better known as Calamity Jane. Rough, hard-drinking, and larger-than-life, Jane drifted through frontier posts like Fort Laramie, often working as a laundress, cook, or occasionally in less respectable trades. She was a familiar figure around the Hog Ranch, where her wild spirit, salty language, and fearless nature earned her both admiration and notoriety.

Her frequent companion, James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok, was also no stranger to Fort Laramie and its outlying haunts. A famed gunfighter, lawman, and gambler, Hickok’s presence added to the Hog Ranch’s reputation as a place where the West’s most legendary personalities could be found rubbing shoulders with soldiers, drifters, and fortune seekers. Though their relationship has been the subject of myth and embellishment, Calamity Jane and Wild Bill became inseparable in Western lore—symbols of the danger, freedom, and unpredictability of frontier life.

The Three Mile Hog Ranch thus stands as more than a relic of frontier vice; it is a reminder of how legendary figures like Calamity Jane and Wild Bill Hickok shaped, and were shaped by, the rough-and-tumble culture of the American West.

Colonel Henry Dodge once painted an unforgettable picture of Calamity Jane as she strode across the parade ground at Fort Laramie—spurs jangling, chaps swinging, and a wide sombrero pulled low. He described her as “a regimental mascot who didn’t know the meaning of the word morals.” Jane’s presence was as unrefined as it was magnetic, and before long, she left the post alongside Colonel Dodge and the Black Hills Expedition, blazing a path north along what is now U.S. Highway 85 into South Dakota—riding, quite literally, into legend.

Meanwhile, just three miles from the fort, the infamous Three Mile Hog Ranch flourished. The name was fitting—close enough for soldiers to stagger to on foot, even through the biting winds and snow of a Wyoming winter, yet far enough from the fort to remain outside the strict eye of military authority. The term “hog ranch” was a less-than-polite euphemism for a brothel, and this one earned its reputation quickly. Gambling tables, whiskey bottles, and the company of at least a dozen prostitutes ensured that soldiers looking for diversion would find plenty of it.

The Hog Ranch became infamous not only for its excess but for the colorful characters who passed through its doors. For the garrisoned soldiers, it was a place to burn off pay and raise hell, no matter the season. Frostbite, hangovers, and disciplinary lashings were a small price to pay for a night’s escape into the bawdy world of one of the last military bordellos in the American West.

There were originally between 12 and 15 buildings on the Hog Ranch site, all erected between 1873 and 1885, including a billiard hall, eight two-room cabins, called cribs, where the ladies plied their trade, a blacksmith shop, a large sod corral with hay and grain available, and a barn with narrow vertical openings in the sides called loopholes, through which a rifle could be used to defend the property and its residents in case of attack from the Sioux, who had, for many legitimate reasons, been on the warpath ever since the Grattan Massacre of 1854.

| SCANDAL ON THE PLAINS

The Hog Ranch did not go unnoticed by those stationed at Fort Laramie. U.S. Army Lieutenant John Gregory Bourke—a prolific writer who kept detailed diaries of his service from 1872 until his death in 1896—painted a particularly harsh picture of the place:

“Several times, on mild afternoons, Lieut. Schuyler and myself went riding, taking the best road out from the post. Three miles and there was a nest of ranches—Cooney’s, Ecoffey’s, and Wright’s—tenanted by as hardened and depraved a set of witches as could be found on the face of the globe. It was a rum mill of the worst kind, with half a dozen Cyprians, virgins whose lamps were always burning brightly in expectancy of the coming of the bridegroom, and who lured to distraction the soldiers of the garrison. In all of my experience, I have never seen a lower, more beastly set of people of both sexes.”

By 1877, both Jules Ecoffey and Adolph Cuny—the original founders—were dead. Ecoffey was killed on November 26, 1876, in an attack by a man named Stonewall Spring. Less than a year later, on July 22, 1877, Cuny was murdered near present-day Chugwater, Wyoming. He was shot in the back by an accomplice of Clark Pelton, a road agent Cuny had been deputized to arrest after Pelton’s gang robbed a stagecoach on the Cheyenne–Deadwood line, killing a passenger. Cuny’s death marked a grim milestone: he is remembered as the first peace officer in Wyoming to die in the line of duty. He left behind a wife and seven children.

Even after the violent deaths of its founders, the Hog Ranch remained a hub of activity. A hotel operated by the Black Hills Stagecoach Company stood alongside the brothel, and together the two enterprises kept business steady until 1887, when the stage line was finally abandoned.

Just a few years later, Fort Laramie itself was shuttered. On March 2, 1890, the last two companies of the Seventh Infantry marched away, leaving the post silent after more than four decades of frontier duty. The following month, on April 9, soldiers from Fort Robinson in Nebraska auctioned off the fort’s buildings and furnishings, raising a mere $1,395. With the garrison gone and commerce drying up, the Three Mile Hog Ranch collapsed as well, scattering its “inmates” to the thriving red-light districts of Cheyenne, Sidney, and Deadwood.

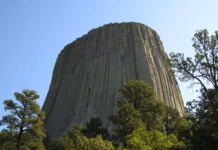

By the time the site was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975, only two buildings were left standing: a wooden barn, and a distinctive U-shaped structure built in 1873 from lime grout—a primitive form of concrete made by mixing sand from the nearby Laramie River with local limestone. Remarkably, this same material is still used today by preservation crews at Fort Laramie to repair cracks and patch the fort’s surviving historic buildings.

This building housed the bar, where soldiers spent their pay on rotgut whiskey, cheap beer, and card games when they weren’t entertained by the establishment’s women in their cribs.

On the nomination form to the National Register of Historic Places nomination form, the writer states:

“To understand just how very significant this establishment was, consider the hardships of soldiering on the frontier; the general lack of recreational outlets typical at frontier forts; a lack of eligible women for marriage, yet hundreds of available soldiers; the illegality of alcoholic beverages on military reservations periodically in the 1870s and 1880s; the only town of any size some 85 miles away; the monotony; the boredom. There was a definite need for a social outlet–it existed at the Three Mile Ranch.”

Today, the remains of the Fort Laramie Three-Mile Hog Ranch are crumbling, abandoned to time and the vagaries of Wyoming weather, but still well worth driving past as you leave Fort Laramie and travel down County Road 52/Road 90 as it follows the winding Laramie River on its course.

The ranch is now private property, so be courteous and watch for rattlesnakes. Keep your eyes peeled and your ears open, and, on the undercurrents of the never-ending Wyoming wind, you might hear distant music and laughter as soldiers still gamble and drink away their fortunes in the now abandoned buildings, the crack of Calamity Jane’s blacksnake whip as she earns her nickname, dressed in a soldier’s blue suit and straddling a mule on her way to her destiny in the Black Hills of South Dakota, or chance upon the spirits of one of the at least eight people who died on the property, many of them shot by Ecoffey or Cuny before they succumbed to violence.

Now grab your camera, hop in the car, and see another great part of eastern Wyoming.

| DIRECTIONS

The building believed to contain the Bar, the Kitchen, and the Black-smith shop is pictured in these images. It’s the only building still standing on the property precisely because it was built from thick-wall limestone grout.

The location is three miles west of Fort Laramie on County Road 90. Visitors are not welcome on the property, but it’s possible to see the area, not the actual building, from a public gravel road that turns North of the location.

| RESOURCES

Story by: Kathrine Rupe

Photography by: Hawk Buckman