| WYOMING |

Archaeologists have assumed that the first Americans were the Clovis peoples who reached North America some 13,000 years ago from northern Asia based on lithics found in North America over the past century. But, that hypothesis changed when new archaeological finds established that humans reached the Americas thousands of years before.

These discoveries, along with identifications in genetics and geology, have forced a reconsideration of where these pioneers came from and when they arrived.

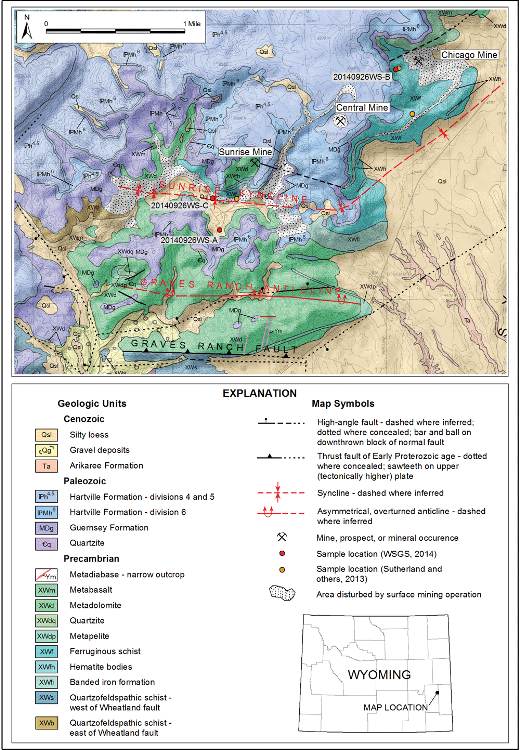

Over the past decade, the Clovis First model has faced increasing scrutiny due to discoveries spanning from southern Texas to the Pacific Northwest. Now, Sunrise, Wyoming joins that list. Through a combination of serendipity, rigorous science, and hard work, the site’s Paleo-Indian ochre mine—the oldest in North America—is shedding new light on when humans first arrived on the continent.

Nearly 13,000 years before the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company arrived in the high desert foothills of eastern Wyoming to establish Sunrise—and long before the removal of more than 40 million tons of iron ore—the first inhabitants of what is now WyoBraska were already harvesting red ocher from the steep walls of Eureka Canyon using antlers and animal bones.

Across nearly every civilization on every continent, from the 75,000-year-old Blombos Cave in South Africa to the modern artist’s studio, red ocher has held a unique place. This vibrant mineral, also known as hematite, was used for body paint, sunscreen, antiseptics, insect repellent, funerary rituals, preserving hides, and decorating cave walls and artworks. Among the broader family of earth pigments—including sienna, umber, yellow, and brown ocher—red ocher has always stood out for its color, significance, and enduring value.

For the Paleo-Indians of the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains, red ocher was essential to daily life. The only known prehistoric quarry of this mineral north of Mesoamerica lies in southeastern Wyoming, about 45 miles from the western Nebraska state line. The Powars II Archeology Site—named for its discoverer and preserver, Wayne Powars—is one of only five such quarries in the Americas and the only known Paleo-Indian red ocher mine in North America. Its story might have been lost to time, had it not been for serendipity, a visionary landowner, and the dedication of archaeologists committed to uncovering its secrets.

| HISTORY OF THE SUNRISE MINE

In the 1880s, the area that would become Sunrise and Hartville, Wyoming, emerged as a hub for copper mining. By 1890, Charles A. Guernsey—whose name honored the nearby town of Guernsey, WY—founded the Wyoming Railway and Iron Company to develop the region’s iron resources. In 1898, the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company (CF&I) began leasing mining rights here to secure a steady supply of iron, and by 1904, CF&I had purchased the entire Sunrise Mine.

Colorado Fuel and Iron, a major steel conglomerate formed through mergers in 1892, was largely controlled by John D. Rockefeller and the heirs of Jay Gould by 1903. While it operated multiple plants nationwide, its primary facility was a steel mill in Pueblo, Colorado, which remained the city’s economic backbone for most of its history.

CF&I aimed to transform Sunrise into a model company town. In the early 1900s, the company built housing, boarding houses, depots, a school, churches, shops, and other structures to support workers and their families. After the public outcry over the 1914 Ludlow Massacre—when Colorado National Guard troops and CF&I private guards attacked a tent colony of 1,200 striking coal miners and their families, killing 21, including children—John D. Rockefeller invested further in the town. These improvements included upgraded brick housing, Wyoming’s first YMCA, parks, playgrounds, modern utilities, a hospital, and additional amenities.

Mining at Sunrise began with strip mining before moving to glory hole mining—a method involving deep shafts, open pits, or block caving to extract ore. The Glory Hole at Sunrise Mine, half a mile wide and now filled with 500 feet of water, stands as a notable example. By World War II, all iron extraction was conducted underground, with ore partially processed on-site at the Shaft-House building before shipment to CF&I’s Pueblo mills for refinement.

Declining ore quality and domestic steel market challenges led CF&I to close the mine and town in 1980, leaving the property abandoned. In 2011, John Voight purchased the site from Fred Ells, remarking that he “bought a mine that came with a town.” Since then, Voight has played a key role in preserving the remaining structures and ensuring archaeologists have full access to this historic site.

| THE DISCOVERY OF POWARS II

In 1986, Wayne Powars (pronounced “powers”) returned to Sunrise, Wyoming, for a school reunion, unaware that fate had a critical role for him to play. Powars had first stumbled upon the quarry as a schoolteacher in 1939 and 1940, and he soon discovered that the site was slated for destruction by the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) under their Abandoned Mine Land Program. Unbeknownst to the DEQ, the mine held extraordinary archaeological significance—information Powars quickly shared with George Frison.

Dr. George Frison, Wyoming’s first State Archaeologist and the only Wyoming resident ever inducted into the National Academy of Science, along with Dr. George Ziemens and Dennis Stanford, Director of the Paleo-Indian/Paleoecology Program at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, acted swiftly to save the site. Powars, threatening to physically block the bulldozers, helped ensure that the demolition was halted just 24 hours before the quarry would have been lost forever—a moment that preserved the oldest known mining operation in both North and South America.

Archaeologists immediately began studying the Powars II quarry, and discoveries continue to this day. Excavations have uncovered over 30 chipped stone tools per square meter, the oldest canid remains ever found at an American archaeological site, and numerous shell beads.

Evidence suggests the Powars II quarry was in use for roughly 3,000 years before its abandonment in favor of a nearby sister site, the Chicago Mine. The Chicago Mine reportedly held floors littered with stone tools and an estimated 250 tons of red ocher when first opened. Unfortunately, industrial mining by CF&I obliterated the entire site, and its priceless artifacts were lost to bureaucracy and commercial interests.

| THE IMPORTANCE OF RED OCHRE AND THE POWERS II SITE

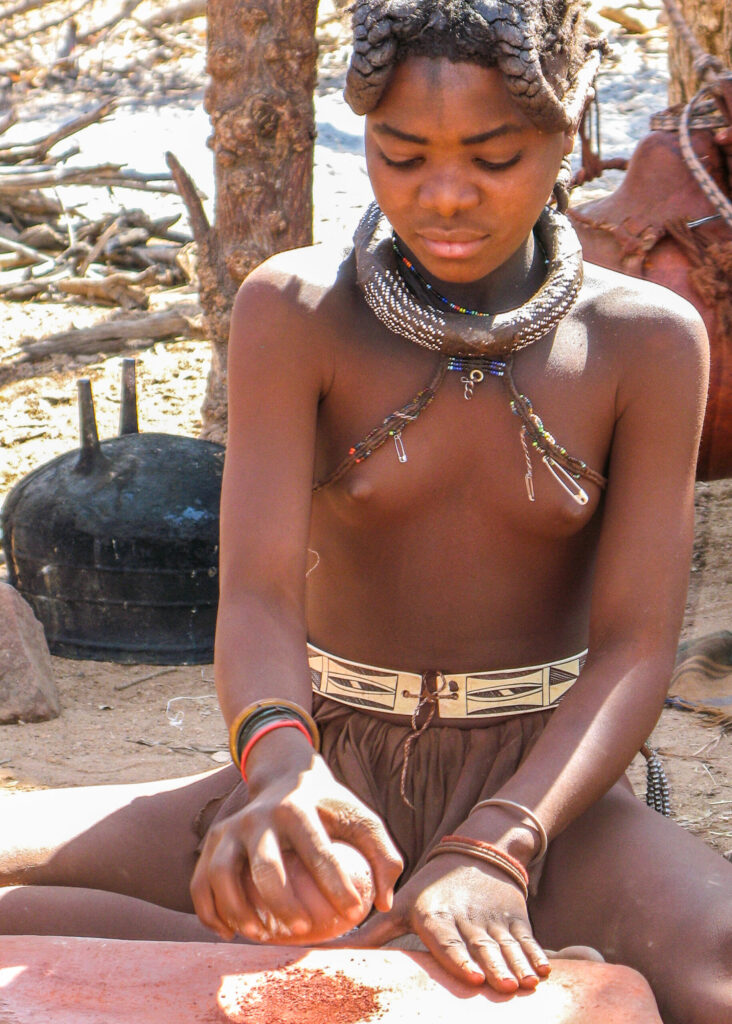

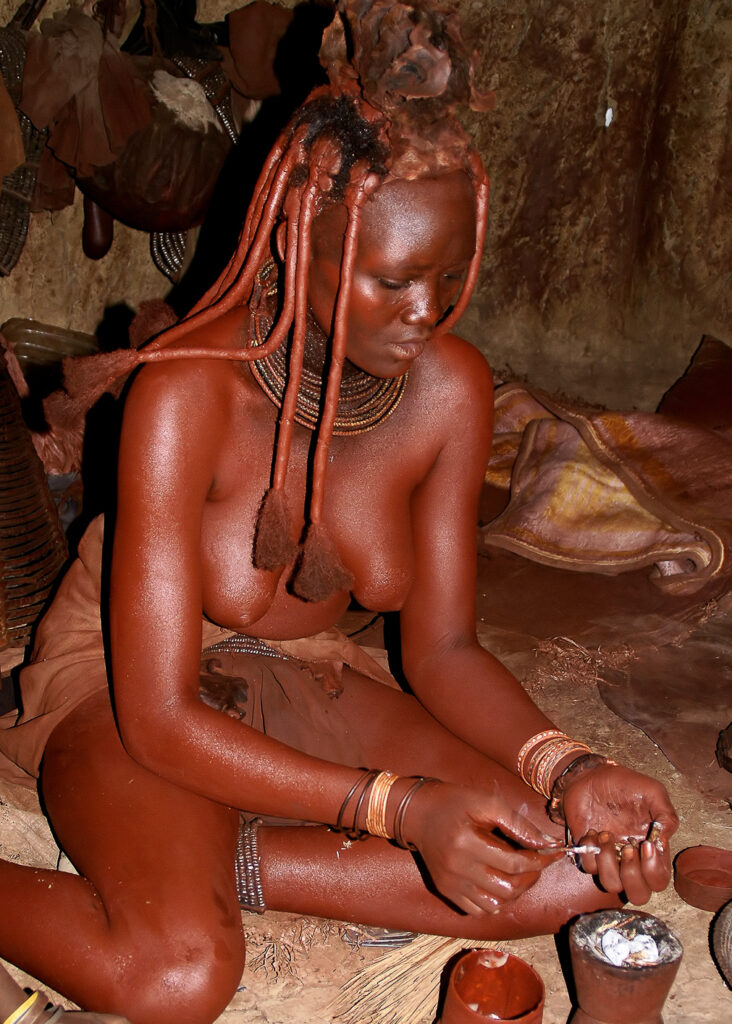

The discovery of a potential pre-Clovis red ochre mine in Wyoming suggests that these early inhabitants used the mineral in ways strikingly similar to other tribal peoples throughout history. Like the Himba of Namibia or their relatives, the Herero, they may have applied red ochre for body decoration, ritual, or practical purposes.

Modern illustrators often struggle to accurately depict pre-Clovis and Clovis peoples. It’s likely that, much like the women of the Himba and other ancient tribes in Africa and South America, these early Americans adorned themselves with red ochre—a practice that provides one of the closest cultural parallels we have for visualizing our prehistoric ancestors.

Himba women adorn themselves in otjize, a mixture of animal fat, ash, and ground red ochre. Anthropologists have speculated about the origins of this practice, with some claiming it is to protect their skin from the sun or repel insects. The Himba say it is an aesthetic consideration, a sort of traditional make-up they apply every morning when they wake. Men do not apply otjize. As pastoralists, cattle are central to the lives of the Himba – just like their relatives, the Herero, who are renowned for the headwear of their women, which resemble cattle horns. The Himba are not the only culture still using red ochre in this manner. Photo by Trails West Magazine Expeditions Photographer © Alun Williams

When Dr. Frison, Dr. Ziemens, and their team of archaeologists first gained access to the Powars II site, they used a backhoe to dig 12 feet into the soil—and were astonished to find lithics dating back 7,000 years. Dr. Ziemens believes even more layers of artifacts remain buried deeper underground.

Radiocarbon dating shows that the quarry was used during two distinct periods. The first, approximately 12,840 years ago, includes the Clovis and Plainview occupations, which lasted several hundred years. During this time, the Clovis people, long thought to be the first inhabitants of North America, quarried red ocher using bones and antlers and also produced and repaired weapons on-site.

The second period, known as the Hell Gap occupation, occurred over a century later. Archaeologists believe some artifacts were intentionally deposited into the quarry pit in what appears to have been a ritual practice, as projectile points were purposefully covered with red ocher.

Clovis projectile points found at Sunrise may have originated as far away as the Edwards Plateau of Texas, stretching from the Hill Country near San Antonio and Austin to West Texas deserts. However, according to Dr. Ziemens, most of the lithics at Powars II were locally manufactured through repeated use of the site over time.

Despite extensive searches, archaeologists have found no evidence of long-term campsites or human habitation on the valley floor near the ocher mine. This absence is likely due to CF&I’s heavy machinery leveling the land to build the town of Sunrise, which pushed and mixed soil layers, disrupting the archaeological record and displacing many lithics.

The team also discovered a previously unknown type of chert, named “Voight Chert” in honor of the current landowner who facilitated access to the site. Paleo-Indians used this chert to fashion Clovis tools for hunting mammoths, camels, and horses. Remarkably, Voight Chert is unlike any other material known to geologists or archaeologists, adding a unique element to the site’s significance.

Michael R. Waters, from the Center for the Study of the First Americans at Texas A&M University, discovered a dirt-stained fragment of blue-gray stone along a grassy Texas creek bank. The stone, strikingly similar to Voight Chert from the Powars II site, was used as a versatile cutting tool before being discarded thousands of years ago. This find is one of thousands of artifacts uncovered in South Texas. If the fragment is indeed Pre-Cambrian and confirmed as Voight Chert, it could indicate remarkable connections between peoples 15,800 years ago.

Dr. George Ziemens notes that 90% of the artifacts at the Powars II ocher mine are made from Voight Chert, suggesting most lithics were crafted on-site and highlighting the significance of Waters’ discovery.

If verified, this find strengthens evidence from other archaeological sites across North and South America, challenging the long-held belief that the Clovis culture was the first in North America. It also raises questions about migration patterns, as these pre-Clovis lithics suggest populations may have arrived independently of the Bering Land Bridge around 15,000 years ago.

The projectile points unearthed at Powars II are unmistakably Clovis in shape and form, fashioned from the unique Voight Chert, found only at Powars II and the Sunrise Mine. Despite their Clovis-like appearance, these points have been temporarily labeled Sunrise Points until additional dating can confirm their age and origin. The edges and fluting of the Sunrise Points show tool marks that may indicate either a developing design concept, repeated ceremonial use, or Clovis points deliberately placed and covered with red ocher in ritual contexts at the mine.

For decades, scientists believed the Clovis people were the first inhabitants of North America. However, discoveries at Powars II and other sites are rewriting this narrative, compelling researchers to reconsider long-standing assumptions about the continent’s earliest populations.

| CREDITS & RESEARCH

- Powars II Paleoindian Hematite Quarry – Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office

- The Red Ocher Mine at Sunrise – Wyoming History

- Further Insights into Paleoindian Use of the Powars II Red Ocher Quarry – American Antiquity

- Research Confirms Eastern Wyoming Paleoindian Site as America’s Oldest Mine – University of Wyoming News

- Interview with Archaeologist Dr. George Ziemens – WyoBraska Magazine

By: Hawk Buckman

Photography by: Alun Williams & Hawk Buckman