| NEBRASKA |

Story & Photography by: Hawk Buckman

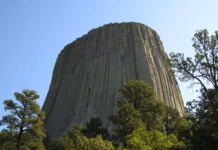

Western Nebraska’s Pine Ridge country looks quiet today. Rugged buttes rise over the White River valley, cottonwoods trace the water’s bends, and pronghorn graze across the open hills. But beneath the calm lies a history every bit as dramatic as the land itself. This is Fort Robinson, one of the most storied military posts of the Northern Plains. It is a place where the U.S. Army’s frontier mission collided with Lakota and Cheyenne resistance, where Crazy Horse met his end, where the Buffalo Soldiers rode, and where thousands of horses, mules, dogs, and even POWs shaped military history.

Today, Fort Robinson is no longer a garrison but Nebraska’s largest state park, and one of the finest preserved frontier military posts in America. The park system has carefully balanced commemoration with recreation: visitors can step into barracks where soldiers once drilled, then mount up for a horseback ride through the same buttes that once hid Lakota warriors. It’s a layered place—part battlefield, part memorial, part vacation retreat. And it remains one of the most compelling destinations in the state for anyone who wants to understand both Nebraska’s story and the wider saga of the American West.

| A FORT IN THE SHADOW OF RED CLOUD AGENCY

Fort Robinson began humbly as Camp Robinson in 1874, established to guard the Red Cloud Agency just west of present-day Crawford. The agency was supposed to distribute rations and annuities to the Oglala Lakota under Chief Red Cloud, who had forced the U.S. to abandon the Bozeman Trail forts a decade earlier. But “peace” was tenuous. Army officers distrusted Lakota leaders; Lakota warriors distrusted the federal promises. Skirmishes were frequent, and the agency agents demanded military backing.

The camp soon hardened into a permanent post, renamed Fort Robinson in 1878, and built to stay. Its mission was twofold: enforce the reservation system and protect trails into the Black Hills. The fort took its name from Lt. Levi Robinson, an Army officer killed by hostile warriors near Fort Laramie. The symbolism was clear—the new garrison was built in the name of sacrifice and military order.

| CRAZY HORSE: DEFIANCE AND DEATH

Fort Robinson began humbly as Camp Robinson in 1874, established to guard the Red Cloud Agency just west of present-day Crawford. The agency was supposed to distribute rations and annuities to the Oglala Lakota under Chief Red Cloud, who had forced the U.S. to abandon the Bozeman Trail forts a decade earlier. But “peace” was tenuous. Army officers distrusted Lakota leaders; Lakota warriors distrusted the federal promises. Skirmishes were frequent, and the agency agents demanded military backing.

The name most indelibly tied to Fort Robinson is Crazy Horse (Tȟašúŋke Witkó), the Oglala war leader who, along with Sitting Bull, had shattered Custer’s 7th Cavalry at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in June 1876. The Army spent the following year hunting down the Lakota and Cheyenne who refused reservation life. By spring 1877, Crazy Horse was isolated, his followers hungry, and his position unsustainable.

In May 1877, he brought his band into the Red Cloud Agency to surrender. For a time he lived peaceably, even sending his wife, Black Shawl, to the fort’s surgeon, Dr. Valentine McGillycuddy, for treatment. But Army officers and Indian agents distrusted him, fearing he would break away north to join Sitting Bull in Canada. By September, rumors swirled that Crazy Horse was plotting escape or renewed war.

On September 5, 1877, soldiers attempted to confine him in the guardhouse at Fort Robinson. Accounts differ in detail, but during the scuffle a soldier’s bayonet pierced Crazy Horse’s side. He died that night inside the fort’s walls. His body was carried away by relatives, his grave kept secret to this day.

For the Lakota, the event remains a profound wound—proof of betrayal and violence in the reservation era. For the Army, it removed one of the last major war leaders resisting U.S. expansion. For Fort Robinson itself, it forever branded the post with the memory of a man whose name still towers in Native and American history alike.

| THE NORTHERN CHEYENNE BREAKOUT

Fort Robinson began humbly as Camp Robinson in 1874, established to guard the Red Cloud Agency just west of present-day Crawford. The agency was supposed to distribute rations and annuities to the Oglala Lakota under Chief Red Cloud, who had forced the U.S. to abandon the Bozeman Trail forts a decade earlier. But “peace” was tenuous. Army officers distrusted Lakota leaders; Lakota warriors distrusted the federal promises. Skirmishes were frequent, and the agency agents demanded military backing.

The fort was the scene of another tragedy less than two years later. In January 1879, a band of Northern Cheyenne led by Dull Knife and Little Wolf, who had been forced south to Indian Territory, attempted to break away and return north. Held under guard at Fort Robinson, the band resisted orders to move. When soldiers cut off food, the Cheyenne attempted escape.

The resulting fight left dozens of Cheyenne men, women, and children dead in the snow around the fort. Survivors were eventually allowed to continue north, but the “Cheyenne Outbreak” stands as one of the darkest episodes in the fort’s story—a stark reminder of how federal policy squeezed Native peoples to the point of desperation.

As the frontier “closed,” Fort Robinson remained active but its purpose shifted. By the early 20th century it hosted Buffalo Soldier regiments, including the 9th and 10th Cavalry, giving Black troops a crucial role in Plains service.

In 1919, the fort became the Army’s Quartermaster Remount Depot, the largest in the nation. Thousands of horses and mules were bred, trained, and shipped out to posts worldwide. The vast parade grounds and stables, many still standing, date to this era. Even after mechanization, cavalry mounts remained essential for years, and Fort Robinson was the backbone of supply.

During World War II, the post took on new roles. It hosted a major K-9 Corps training center, where thousands of war dogs and handlers prepared for service. It also became a German prisoner-of-war camp, housing captured soldiers from Europe. These mid-century chapters added new layers of history, extending the fort’s life well past the frontier days.

| THE END OF THE GARRISON AND THE BIRTH OF A PARK

Fort Robinson began humbly as Camp Robinson in 1874, established to guard the Red Cloud Agency just west of present-day Crawford. The agency was supposed to distribute rations and annuities to the Oglala Lakota under Chief Red Cloud, who had forced the U.S. to abandon the Bozeman Trail forts a decade earlier. But “peace” was tenuous. Army officers distrusted Lakota leaders; Lakota warriors distrusted the federal promises. Skirmishes were frequent, and the agency agents demanded military backing.

After the war, Fort Robinson’s military value ebbed. In 1948 the Army closed the post and transferred it to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which operated a beef cattle research station on the grounds. The sturdy brick barracks became labs, offices, and dorms.

By the 1950s, Nebraskans recognized the site’s heritage potential. In 1956, the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission acquired key buildings and land, formally establishing Fort Robinson State Park. Expansion continued through the 1970s, with historic preservation projects and the addition of surrounding acreage in the Pine Ridge escarpments. Today, at 22,000 acres, it is Nebraska’s largest state park.

This transition was not just bureaucratic. It marked a shift from military governance to public stewardship. The Nebraska Game and Parks Commission balances preservation of historic structures—guardhouses, officers’ quarters, stables—with recreation, ranging from horseback rides to jeep tours. Where soldiers once patrolled, families now camp, hike, and fish. The park’s administration works closely with historians, Native representatives, and local communities to keep the site’s history alive while ensuring it remains accessible to everyday visitors.

Step onto Fort Robinson’s parade grounds, and history is still palpable. Rows of late 19th- and early 20th-century brick buildings line the wide lawn. The Post Headquarters, built in 1905, now houses the Fort Robinson History Center, where exhibits trace the fort’s Indian Wars, the death of Crazy Horse, the Cheyenne breakout, the Remount era, and World War II. Artifacts, maps, and interpretive displays lay the groundwork for understanding what happened on the surrounding ground.

Walk a short distance, and you’ll find the guardhouse, where Crazy Horse was mortally wounded. A marker identifies the site, and while the building is gone, the space itself carries weight. Further out, the Cheyenne Outbreak marker recalls the 1879 tragedy.

For those with more time, the park offers immersive experiences. You can stay in former barracks or officers’ quarters, now converted into modern lodging. Horseback rides trace trails through the buttes; jeep tours climb ridges with sweeping views; stagecoach rides offer a taste of 19th-century transport. Herds of bison and Texas longhorns roam the park’s prairies, adding a living link to Plains ecology.

The University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Trailside Museum, on park grounds, adds a scientific dimension with exhibits on fossils and geology—including the famous “Clash of the Mammoths” skeletons found nearby.

In summer, the park hosts rodeos, pageants, and re-enactments, blending entertainment with education. Trails thread into the Pine Ridge, offering hikes for those who want solitude and scenery alongside history. For many visitors, the appeal lies not just in the history but in the ability to camp, fish, or simply sit beneath the wide Nebraska sky and imagine the generations who lived and died here.

| THE ROLE OF NEBRASKA GAME AND PARKS

Fort Robinson began humbly as Camp Robinson in 1874, established to guard the Red Cloud Agency just west of present-day Crawford. The agency was supposed to distribute rations and annuities to the Oglala Lakota under Chief Red Cloud, who had forced the U.S. to abandon the Bozeman Trail forts a decade earlier. But “peace” was tenuous. Army officers distrusted Lakota leaders; Lakota warriors distrusted the federal promises. Skirmishes were frequent, and the agency agents demanded military backing.

The Nebraska Game and Parks Commission shoulders the challenge of maintaining Fort Robinson as both a historic site and a state park. This means funding restoration of aging brick barracks, stabilizing ruins, and interpreting sensitive history—particularly episodes like the death of Crazy Horse and the Cheyenne outbreak. It also means building trails, managing herds, running campgrounds, and marketing the site as a tourist destination.

The commission’s stewardship ensures that the fort is not locked away as a sterile monument but instead lived in and experienced. Families might come for horseback riding and end up learning about Crazy Horse; history buffs might arrive for the Indian Wars exhibits and leave with memories of hiking through red rock canyons. This dual role—guardian of heritage and promoter of recreation—makes the park one of Nebraska’s flagship destinations.

| WHY FORT ROBINSON STILL MATTERS

Fort Robinson began humbly as Camp Robinson in 1874, established to guard the Red Cloud Agency just west of present-day Crawford. The agency was supposed to distribute rations and annuities to the Oglala Lakota under Chief Red Cloud, who had forced the U.S. to abandon the Bozeman Trail forts a decade earlier. But “peace” was tenuous. Army officers distrusted Lakota leaders; Lakota warriors distrusted the federal promises. Skirmishes were frequent, and the agency agents demanded military backing.

For some, Fort Robinson is simply a scenic getaway. For others, it is sacred ground, tied to painful memory. For historians, it is a key outpost in the narrative of the Plains Indian Wars and the transition to 20th-century military logistics. What unites these perspectives is the recognition that history is not abstract here—it’s built into the landscape.

The fort teaches lessons about U.S.–Native relations, about how federal policy could both promise peace and deliver violence. It shows the endurance of Native peoples in the face of forced removals. It also tells of the Army’s adaptability, shifting from frontier patrols to horse breeding to canine training to POW management. And it demonstrates Nebraska’s commitment to preserving such a layered story for the public.

At Fort Robinson, you cannot escape the ghosts of the past—but you also cannot miss the vitality of the present. Families ride, children laugh, visitors camp. And always, the buttes watch, silent witnesses to it all.

Planning a Visit

Where: Near Crawford, Nebraska, on U.S. Highway 20.

Size: ~22,000 acres, Nebraska’s largest state park.

Key Attractions: Fort Robinson History Center, guardhouse site of Crazy Horse’s death, Cheyenne Outbreak markers, Trailside Museum, bison and longhorn herds, horseback and jeep tours, restored barracks lodging.

Best Time: Summer offers the most programming; fall brings quieter trails and striking colors in the buttes.

Why Go: To experience the living intersection of history, landscape, and recreation.

Fort Robinson is not a simple story of frontier forts and fading glory. It is a living crossroads of history and memory, where Crazy Horse’s defiance, the Cheyenne’s desperation, the Army’s evolving mission, and Nebraska’s commitment to preservation all converge.

As a destination, it offers the rare chance to stand where the defining struggles of the Plains played out and then to ride a horse into the same hills, sleep in the same quarters, and wake to the same sunrise. Few places in the American West let you inhabit the past and present so completely.

For Nebraska, Fort Robinson is more than a park. It is a reminder, a memorial, and a living legacy. For visitors, it’s a journey worth making—because here, history isn’t just told, it’s still alive.

| RESOURCES & REFERENCES