| TRAVEL |

Story & Photography by: Hawk Buckman

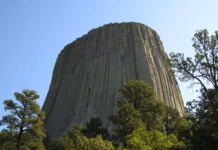

Tucked into the Southern Black Hills, Hot Springs, South Dakota, wears two coats at once: spa town and science hub. On one side of town, naturally warm, mineral-rich water still bubbles up as it has for millennia, the reason nineteenth-century visitors flocked here to “take the waters.” On the other, a yawning Ice Age sinkhole—frozen mid-catastrophe—holds the densest concentration of Columbian mammoth remains yet found, preserved in place beneath a protective building that doubles as a working dig and a museum. The interplay is stark and honest: life-giving water drew people to settle here, and that same pull lured Pleistocene giants to their doom. That’s Hot Springs—no fluff, just the real story.

The town’s name is literal. Dozens of small artesian vents and one larger spring rise from fractured limestone, warming a creek that snakes through the valley. In 1890, entrepreneur Fred Evans covered a huge spring with what became Evans Plunge, a bathhouse and indoor pool that turned Hot Springs into one of the Black Hills’ earliest tourist magnets. The Plunge still operates today, heated naturally to the high 80s (°F), a reminder that long before interstates and influencer road trips, people came here for simple, steady reasons: clean air, a decent bed, and warm water that eased bad backs and miner’s aches.

That water is key to understanding the region’s deeper past, too. The same karst geology—limestone riddled with joints and cavities—can collapse into steep-sided basins. Fill one of those with groundwater, then add thirsty Ice Age herbivores, and you get the story that put Hot Springs on the scientific map.

In 1974, a developer was leveling a hill on the south edge of town for a new subdivision when his equipment bit into something pale and curved. It wasn’t a root; it was a tusk—over six feet long. Work stopped. Paleontologists moved in. Ten days later, with nothing more than shovels, brushes, and discipline, they had exposed a startling tangle of massive bones—skulls, limb elements, ribs, and more—lying just as death and mud had left them. The housing plan died right there. A nonprofit was organized, a building went up over the bonebed, and The Mammoth Site became a working excavation that the public could walk into and around. That “see-the-dig, not just the display” model is part of why the place hits harder than a typical museum.

Geologically, the trap was brutally simple. During the late Pleistocene, a cavern roof in the Madison Limestone collapsed, forming a steep, slick-sided sinkhole roughly the size of a football field. Groundwater and surface runoff filled it to create a deep, warm pond fringed with soft, churning sediments. Big herbivores—especially mammoths—were drawn in for a drink or a wallow. Getting down was easy. Getting out was not. Splayed footprints and bone orientations suggest animals floundered in the muck, exhausted themselves, and died; their carcasses settled into pond sediments that later dried, compacted, and gently entombed the bones in place. Over years and centuries, the basin acted like a one-way gate, a “deep-time watering hole” that culled the unlucky and the inexperienced.

SDPB

Mindat

You’ll hear the refrain that most mammoths here were young males. That tracks with modern elephant behavior: teenage and twenty-something males, recently pushed out of matriarchal herds, take more risks and make more mistakes. The bonebed bears that out. The result wasn’t a single catastrophe but a grim tally across many seasons—a natural hazard operating on slow burn.

Dating the site has taken multiple passes. Early radiocarbon ages from bone apatite suggested roughly 22,000–26,000 years before present, but that method is now considered unreliable for this context. Later work used other techniques, including uranium-series dating on tooth material and luminescence dating of sediments. Those results indicate the sinkhole and its fossil fill are considerably older—on the order of ~130,000 years, with some studies bracketing fossil ages broadly between ~140,000 and 190,000 years. Translation: we’re likely looking at an interglacial or warm phase when megafauna congregated around ever-reliable water. That’s consistent with the warm-spring setting and with the animal cast found in the sediments.

| MAMMOTHS

The headline is mammoths—primarily Columbian mammoths (Mammuthus columbi), the tall, warm-adapted cousins of the woolly mammoth, with a scattering of woollies in the mix. The count has climbed as the dig advances: more than 60 mammoths documented—one of the richest single-site mammoth tallies anywhere. But pay attention to the quieter bones and shells along the walkways: the pond also trapped or collected parts of Ice Age camels and llamas, canids like coyotes and wolves, small carnivores, rodents, birds, and an invertebrate suite that includes freshwater clams and snails. It’s a full ecosystem in cross-section, frozen mid-routine—who drank, who hunted, who scuttled along the shallows.

One of the site’s strengths is honesty. Bones aren’t yanked out, glued, and mounted into hero poses. They’re left where they were found—supported by the sediments that held them for thousands of years. That in-situ philosophy forces you to slow down, read the layers, and see the physics of death: a scapula canted downhill, ribs splayed by bloating, a tusk curved like a question mark where the head settled. It’s instructive and a little sobering.

Unlike many digs that vanish behind fences until a paper hits a journal, The Mammoth Site invites people into the process. You can walk catwalks over the active bonebed, watch technicians prepare fragile pieces in the lab, and see research updates summarized for non-scientists. School programs and summer “junior paleontologist” experiences keep the pipeline full—future field techs learning how to trowel, bag, and log instead of just snapping selfies. That’s not theater; it’s the right way to build a durable respect for evidence. The museum’s controlled climate and year-round work schedule mean the bonebed stays stable while the science moves forward.

Make time for the rest of town. Downtown Hot Springs wears warm-hued sandstone buildings from the 1890s, including the still-used City Hall and the former schoolhouse now housing local history collections. The scale is human, the sidewalks are walkable, and the pace is sane. Between the springs, the architecture, and the Mammoth Site, the place hangs together as a coherent story: water, stone, and time.

And yes, the bathing culture isn’t just a sepia photograph. Evans Plunge still draws families and lap-swimmers to soak, splash, and work the kinks out under arching beams—same idea as 1890, fewer mustaches. If you want the “why Hot Springs?” answer in ten seconds, step into that 87-degree pool and then go stand above the bonebed where water once spelled death. Same resource; different outcomes. That kind of clarity sticks with you.

The Mammoth Site is housed inside an insulated structure built over the bonebed, which means you can visit any season without worrying about weather. Exhibits ring the active excavation floor; catwalks let you look down into the sediments at skulls, tusks, pelvises, and limb bones exactly where they came to rest. Guided tours run throughout the day, and you’ll see real tools and field notes, not just glossy wall text. Hours vary by season (longer in summer, shorter in winter), so check the museum’s official schedule before you set out. If you’re planning a family trip that blends learning and straight-up fun, pair the Mammoth Site with a soak at Evans Plunge and a walk downtown. It’s a tightly packed day with no dead time.

First lesson: nature isn’t sentimental. A warm pond can be a lifeline or a lethal trap depending on the slope of the bank and the weight of the drinker. Second: evidence beats speculation. Early dates based on bone chemistry looked neat on paper but turned out shaky; better methods corrected the timeline without changing the core story. Third: context matters. Because the Mammoth Site left bones in place, scientists can read behavior from geometry—who slipped where, how carcasses shifted, how water levels rose and fell. It’s the difference between a skeleton and a scene.

There’s also a forward-looking angle worth stating plainly. We’re still only partway into this deposit. Researchers estimate the sinkhole may hold remains from scores more mammoths and a expanding list of associated fauna. As techniques improve—microstratigraphy, sediment DNA, isotopic work—we’ll wring more climate and behavior data out of what looks like plain mud to the untrained eye. That’s the right way to honor a site like this: careful excavation, conservative claims, and public access that shows the work.

Hot Springs isn’t a gimmick town. It’s a place where geology writes the rules—limestone collapses, water warms, animals gather, some perish, and, a hundred thousand years later, people learn. The Mammoth Site isn’t just a collection; it’s an argument for patience and craft in a noisy world. If you want spectacle, you’ll get it—there’s nothing quite like staring into the eye sockets of a Pleistocene giant that died exactly where you’re standing. If you want substance, you’ll get that, too—layered sediments, revised dates, and the uncomfortable truth that nature doesn’t grade on a curve.

Come for the warm springs, stay for the cold facts. That’s Hot Springs, South Dakota: past and present, straight up.

| REFERENCES & MORE INFORMATION

- The Mammoth Site History

- City of Hot Springs History

- Wikipedia: The Mammoth Site

- Carnegie Museum: The Mammoth Site

- Black Hills & Badlands: The Mammoth Site

- Evans Plunge Official Website

- PBS: Images of the Past – Palace Plunge & Evans Plunge

- SDPB: History of Hot Springs Bathhouses

- SDPB: Discovering the Hot Springs Mammoth Site in 1974

- Mindat: Mammoth Site, Hot Springs, SD

- USGS: Bringing South Dakota’s Southern Black Hills Mammoth Site Formation and Fossil Discovery to Light

- ResearchGate: Mammuthus primigenius Remains from the Mammoth Site of Hot Springs, South Dakota

- All Black Hills: Mammoth Site of Hot Springs

- Business Insider: A Sinkhole in South Dakota is Packed with Mammoth Fossils