| NEBRASKA |

Story & Photography by: Hawk Buckan | 500px

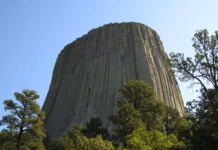

When I first moved to western Nebraska from Colorado, I carried with me the memory of seeing bald eagles in the high country each fall. Up there, around Trap Lake and Chambers Lake, I was used to watching them before the ice closed in. So when I began spotting them out on the plains, I was both stunned and a little confused. At first, I didn’t bother to learn why they were here; my only concern was finding them and documenting them through the lens of my camera.

Only later did I begin to understand their purpose in western Nebraska — and with that knowledge came the ability to find them more efficiently. People often ask me how I get so close for the photographs I take. The truth is, I don’t. The only way is through a long lens. Out here, bald eagles have zero tolerance for people.

That’s not the case everywhere. On the West Coast — Oregon, Washington, Vancouver, even up through Alaska — bald eagles behave almost like “rats with wings.” Along the docks and piers, they’ll engage with humans, scavenging fearlessly in plain sight. Western Nebraska is different. Here, the eagles remain wild, wary, and unapproachable, which makes photographing them both a challenge and a privilege.

Every winter, these wary birds transform Nebraska’s rivers and reservoirs into staging grounds for one of the Great Plains’ most dramatic natural events: the return of the bald eagles. Icons of wilderness and resilience, they concentrate along the Platte, North Platte, and reservoirs like Lake McConaughy, drawn by three things — food, open water, and safe roosting. When the northern lakes and rivers freeze solid, Nebraska becomes their refuge.

| WINTER STRATEGY

Not all bald eagles migrate. Some stay resident if food remains available, but for northern breeders — from Alaska, Canada, and the Great Lakes — deep freezes make survival difficult. When rivers seal under ice and fish become inaccessible, eagles shift southward in search of open water. Nebraska’s hydroelectric dams, managed releases, and large reservoirs keep sections of water open even in harsh winters, drawing both fish and waterfowl. This dependable refuge explains why eagles gather here every December through February.

Eagles are opportunistic: they hunt live fish, catch waterfowl, and scavenge carrion. What makes Nebraska attractive is concentration. Open stretches of tailwater below dams funnel fish into smaller areas, while rafts of ducks and geese crowd the same waters. For a predator conserving calories in winter, this means efficiency. At Lake McConaughy and Lake Ogallala, Kingsley Dam’s hydroplant releases keep water ice-free, providing a buffet for dozens of eagles each January and February.

Food alone doesn’t define wintering habitat. Eagles also need safe places to rest. Western Nebraska’s river corridors — lined with mature cottonwoods and shelterbelts — supply ideal communal roosts near feeding areas. These tall trees provide visibility, shelter from wind, and safety from predators. With relatively low human density in the Panhandle, eagles can roost undisturbed while still staying close to food.

| A MIGRATION CORIDOR

Western Nebraska lies within a natural mid-continental corridor. Eagles from as far as Alaska and Canada funnel along the Platte and North Platte rivers, stopping where conditions are favorable. State wildlife agencies consistently note that the birds mix here: young subadults, mature adults, and transients from multiple origins. The result is not just a migration stopover but a winter congregation site.

Eagles have long used Nebraska as a winter base. A USGS study in the early 1980s recorded roughly 200 wintering along a 370-kilometer stretch of the Platte and North Platte rivers. Since then, numbers have risen with the species’ national recovery. Nebraska now records both higher winter counts and an increase in breeding pairs, reflecting decades of conservation successes since the DDT bans and habitat protections of the 1970s.

For birdwatchers, western Nebraska offers reliable viewing spots:

- Lake McConaughy & Lake Ogallala (Kingsley Dam) — Prime January–February habitat where hydro releases prevent ice. A designated eagle-viewing facility overlooks the tailwaters.

- Sutherland Reservoir — Open water near North Platte draws both eagles and large flocks of waterfowl.

- Harlan County Reservoir — Another concentration site when surrounding waters freeze.

- Platte River corridor — Known roosting habitat in mature cottonwoods.

The best time to visit is mid-winter, particularly January and February, when freezing elsewhere forces eagles to cluster around Nebraska’s open waters.

| BEHAVIOR AND SPECTACLE

Winter gatherings showcase eagle behavior rarely seen elsewhere. Adults dominate prime feeding areas; subadults linger at the margins. They hunt ducks, dive for fish near ice edges, and often scavenge. It’s common to see disputes — aerial chases or mid-air grappling as one bird attempts to steal another’s catch. Roost sites may hold dozens of birds in a single grove of trees, silhouetted against the winter sky.

That such gatherings exist at all is a conservation story. Bald eagles, once near extinction, have rebounded due to strong legal protections, pesticide bans, and public investment in habitat. Nebraska’s winter concentrations testify to that rebound. But they also reveal vulnerabilities: birds are clustered in relatively small areas, making them sensitive to habitat loss, poisoning from lead shot, and disturbance from human activity. Maintaining open-water habitats and preserving old cottonwoods are critical to keeping these winter roosts viable.

The future of eagle migration through western Nebraska depends on balancing infrastructure, agriculture, and wildlife. Dams and power plants, often criticized for their ecological impact, ironically create much of the open water that sustains winter eagles. Working with irrigation districts to preserve flow patterns, encouraging non-lead hunting ammunition, and protecting riparian forests will secure the state’s role as a winter refuge.

For Nebraskans, the arrival of bald eagles is more than a seasonal curiosity. It ties the region to vast northern forests and Great Lakes landscapes, reminding us that conservation must function across borders. And for travelers, few sights equal a line of eagles rising over frozen water, their white heads catching the midwinter sun.

| RESOURCES & REFERENCES

- Eagle Viewing Facilities — Central Nebraska Public Power & Irrigation District (Kingsley Dam viewing info)

- Lingle, G.R. (1986). Winter ecology of bald eagles in southcentral Nebraska — U.S. Geological Survey

- Bald Eagle — Nebraska Game and Parks Commission (species overview & viewing tips)

- Lake McConaughy — Top Birding Sites, OutdoorNebraska (wintering congregation information)

- Bald Eagles Take Refuge at Sutherland Reservoir — Nebraska Public Power District (press release)

- 6 Spots in Nebraska to Get a Birds-Eye View of Bald Eagles — Visit Nebraska (viewing sites guide)

- Groundbreaking study finds widespread lead poisoning of bald and golden eagles — USGS (lead poisoning impact)

- Lead Bullets Are Stunting the Bald Eagle’s Recovery — Audubon (analysis & conservation implications)

- Pain, D.J. et al. (2019). Effects of lead from ammunition on birds and other wildlife — Environmental Research (review)

- Busch, D.E. (1981). Wintering Bald Eagles at Southwest Nebraska Reservoirs — Nebraska Bird Review (historical survey)