| NEBRASKA |

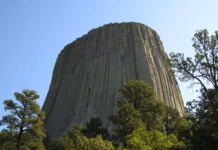

Traveling south along highway 71 into Scotts Bluff County, you begin to see the scope and size of the North Platte Valley begin to open up to eye-popping vistas of the valley floor. Large buttes dominate the valley’s center, surrounded by the ponderosa pine-covered Wildcat Hills to the South. To the Southeast, large mounds of rock dot the skyline, forcing the viewer to take a breath in awe of its splendor.

As you enter the North Platte River Valley, you quickly realize that these large buttes differ from the mountains to the west. Upon closer inspection, they seem softer and more relaxed.

Rising about 400 feet from the surface of the Earth, these buttes are large. Most buttes dotted throughout the Midwest are only a few hundred feet tall and are generally not very wide at the top. But the buttes in Scotts Bluff County stand out as landmarks and have since the heady days of early fur trappers and the immigrant trails.

Each butte in Scotts Bluff County has a name like Castle Rock, Independence Rock, and Saddle Rock. But the most recognized is Eagle Rock which sits on the Northside of Hells’ Gate on the East side of Scotts Bluff National Monument.

Standing at the base of Eagle Rock, you can see something unique about the geology that created these rock formations.

The three kinds of rock identified by geologists make up the geological structure of the buttes that dominated the North Platte River Valley in western Nebraska. Sedimentary (sea bed, river, and dune deposits), igneous (volcanic), and metamorphic (rocks that have been changed by pressure and heat). Sedimentary rocks are the only rocks exposed at Scotts Bluff.

The origins of Scotts Bluff began 80 to 55 million years ago during the Laramide orogeny as the Rocky Mountains were formed west of Scotts Bluff. Over millions of years, weathering and wind erosion deposited windblown and water sediments to the east. These sediments accumulated in layers burying what would become the North Platte Valley to a height of over 800 feet. The layers became compressed by overlying sedimentary rocks hardening the material.

||| PIERRE SHALE – THE FOUNDATION OF THE GREAT PLAINS

At this time, what would become the North Platte Valley was flat, with a few small rolling hills dotted here and there.

Over millions of years, the force of the flow of water from newly formed rivers, wind, and weathering erosion began to cut the valley out of the overlaying rock exposing layers of sedimentary rock which geologists have been able to date to 34 to 20 million years.

Geologists use a system to identify the rock layers that work like reading book chapters. Each layer reveals different characteristics based on color, grain size, composition, and material thickness, allowing for accurate material dating.

If you dig 250 feet below the North Platte River, you would encounter a thick layer of shale, evidence of a shallow sea that once covered the Great Plains until 70 million years ago. The sea began to recede as the Rocky Mountains, and the Great Plains began to uplift.

The shale formed at the bottom of the sea and is now the foundation of the promontories surrounding Scotts Bluff. Geologists named this formation the Pierre Shale.

Newly formed rivers and eastward-blowing high winds began carrying weathered sand and silt from the mountains depositing it across western Nebraska.

The sediments deposited by newly formed rivers became the Orella Member of the Brule Formation in the White River Group, which can be viewed in the badlands north of Scotts Bluff National Monument.

About 33 million years ago, huge, violent volcanic eruptions ravaged south-central and western Colorado depositing volcanic ash in west Nebraska.

This ash is still visible in the Whitney member of the Brule Formation and is mixed with silt. Two distinct ash layers are found in the Whitney Group. The lower layer most likely records one massive super-eruption about 31 million years ago, possibly from the Yellowstone Super Volcano. These layers are visible on Eagle Rock about halfway up the rock face.

||| TOWERING SAND DUNES ONCE DOTTED WESTERN NEBRASKA

About 20 million years ago, western Nebraska was once again changing. Evidence at Eagle Rock, Saddle Rock, and along the face of the bluffs suggest that dunes once roamed the panhandle of Nebraska. The Gering Formation of the Arikaree Group (top of the bluffs) records the development of these dunes. Cross-sections of the Gering Formation dunes can be seen on Saddle Rock Trail. The “pipy” concretions of hard calcium deposits stick out of the rock layers.

The dunes and concretions “pipy” are scattered together among the layers of sediment, indicating cyclic changes in climate and weather.

During dry periods, the dunes formed to towering heights while winds drove them across western Nebraska. When it rained, the water moved through the calcium carbonate and cemented the sand into concretions.

Renewed uplift of the plains and further decreasing amounts of water-born and wind-blow sediments allowed rivers and wind to erode the sediment layers about five million years ago.

As the uplift of the plains continued, the rocks began to crack and peel away from each other, further weakening them. In some areas, the “pipy” concretion was not cracked resulting in the formation of a protective cap of harder rock over the top of soft rock resulting in what we know today as a bluff.

Before the last uplift of the plains and the Rocky Mountains and the erosion that followed, the Great Plains of western Nebraska were at least, if not more, as high as the present top of the bluffs at Scotts Bluff National Monument.

Over 5 million years of erosion have removed 400 to 800(+) feet of sedimentary rock, and the process continues.